Why and How to Develop Photographic Work in 2025?

Multiplication of Photographic Intentions

Since the invention of photography in the 19th century, the act of taking or viewing a photo has evolved and continues to evolve today depending on the intentions of photographers and viewers. Photographic practices in 2025 are indeed no longer the same as those of Nicéphore Niépce’s darkroom in 1825.

Photographs have long been considered by some as a neutral recording of reality, a trace, an imprint based on a mechanical and chemical process directly capturing the light reflected by objects. Early photographic intentions were primarily documentary and portraiture, aimed at keeping a visual record of places, people, or important events to preserve testimonies of the world for future generations.

Intentions then multiplied: artistic, scientific, advertising, commercial, ideological, educational, touristic, personal, and social.

What intention should be adopted to develop photographic work?

Note that, although artists like Man Ray used photography as early as the 1930s in the service of subjective creativity, theorists in the 1980s, relying on Charles Sanders Peirce's concept of the index, again attempted to conceive of photography as a trace of reality.

Transformation of Our Relationship with Photography

The multiplication of media and social networks, the growing ease of taking, modifying, altering, viewing, sharing, liking, or disliking a photo, along with the recent emergence of AI-generated images, are transforming our relationship with photography.

Today, we take and view photographs daily. The widespread and intensive use of photography has been accompanied by an acceleration in the capture, sharing, and visualization of images. We take spontaneous photos and immediately publish them on social networks. Similarly, we consume images at a frantic pace, often scrolling through them quickly without taking the time to look at them in detail.

The use of photography, both for the photographer and the viewer, seems to become an end in itself, beyond the content of the image. The act of taking or viewing photographs without any other purpose becomes more significant than what the photographs represent.

Has photographic intention simply disappeared?

Taking and viewing photos daily influences the attention we pay to places, objects, and people.

We may take a photograph of a place without taking the time to look at and appreciate the real place, and we may look at photographs on our smartphone on the train without raising our eyes to observe the real landscape we pass through outside the window.

Sometimes, we also experience moments through the lens of a camera or the screen of our smartphone, such as during a show where we constantly check the framing, or when we take photos in a museum without looking at the artworks themselves, only the screen of our smartphone.

Photography gradually replaces our direct, sensory experiences with the physical world, and the photographic space seems, increasingly, to substitute for the real space.

To the question, "What is photography in 2025?" one possible answer would be to consider photography as an alteration, a reduction of our physical and sensory experience of places, objects, and people.

“No thinker would dare say that the scent of hawthorn is useless to the constellations.”

Les Misérables, 1862, Victor Hugo

The Lost Shuttlecock

Why is this badminton shuttlecock here? Was it forgotten, abandoned?

And this fence, am I inside or outside the playing field? Did the children have no way to retrieve it? Did they have to rush home? Were they scolded by a neighbor because they were not allowed to play here?

Observing and questioning evokes narratives, transforming a simple object into endless potential sources of poetry.

At the Expense of Experiential Pleasure: Three Real Examples

The desire to take and share a "beautiful photo" and a "beautiful memory" can tend to restrict and ultimately harm the real experience. Photography can thus lead us to have uncomfortable and unpleasant experiences solely to stage and fabricate our memories.

A photographer might ask a young married couple to pose in a specific location, as the framing allows for a perfect view of the couple in the foreground and the Eiffel Tower in the background, even though the couple is actually miles away from the Eiffel Tower and a pile of trash, out of the frame but nearby, gives off an unpleasant odor.

Will the young couple forget they never actually saw the Eiffel Tower up close and this unpleasant smell when they look at the photo a few years later?

Staging and Fabricating Our Memories

This photographer might also ask the couple to simulate crossing a bridge on the Seine, lifting, and lowering their legs repeatedly and artificially until the perfect shot is achieved.

Will the young couple forget they never actually crossed the bridge and the cramps felt due to this repetitive movement?

In very touristy places, visitors also often prioritize photography over real experience.

For example, tourists at the Itsukushima Shinto Shrine in Japan are willing to wait longer and longer in line to capture the same iconic photo of the famous red Torii, seemingly floating on the water.

What will be the time limit beyond which tourists will give up on the photo and perhaps simply look and enjoy the place?

It is worth noting that tourist photography invites us to reflect on the way visitors choose to photograph.

Why do we all want to take the same photograph?

Does the perfect viewpoint, the only one capable of capturing the essence of a place, exist?

Does a place, by its spatial and formal characteristics, impose, dictate the viewpoint?

Is it the influence of media and social networks? Are we trying to reproduce others' memories?

Note that Serge Tisseron, psychoanalyst and psychiatrist, reminds us in his text Photography Made with Hands (2011) that not understanding or despising tourist photography reflects a misunderstanding of psychic functioning, and that one of the important functions of tourist photography is to allow us, as tourists who, for various reasons, may not have fully experienced the present moment (e.g., due to the pace imposed by tour operators), to relive or reconstruct that moment through viewing photographs with family or friends.

Furthermore, the act of photographing oneself or friends in a public space changes the experience of that space for people who are not involved, those outside the photographed individuals. The positive side of this phenomenon is that everyone smiles around us during our walks; the downside is that photographers sometimes block a passage, forcing us to change our route, or a selfie stick may prevent us from enjoying a landscape.

“I adore the theater. It’s so much more real than life.”

The Picture of Dorian Gray, 1890, Oscar Wilde

Why Take Photographs?

If photography today tends to become a space in itself, devoid of intention, and if it distracts our attention from real space, prompting us to experience it only in a pragmatic and prosaic way, how, conversely, can we envision the photographic act as a means of paying particular attention to what surrounds us?

Can the photographic act be an intentional and aesthetic experience that allows us to live poetically in the world?

Can photography allow us to see and help others see differently, to cast a careful and intentional gaze on details, moments, and emotions that we don't always take the time to notice in our daily lives?

We no longer pay attention to the world and deprive ourselves of an infinite array of possible aesthetic experiences.

Might photography then not be a tool for introspection and investigation of new aesthetic experiences?

Seeking ordinary or unusual presences, imagining worlds as they were, could have been, are, will be, or might be.

Surprise Heuristics and Invite Daydreams

But how to invite the invention of new worlds and offer an aesthetic experience?

We constantly use heuristics, strategies, and mental shortcuts to save time and energy. When we look at an image, our brain seeks to identify and associate it with already acquired experiences or knowledge. A photograph that our brain classifies among what it already knows does not elicit careful reading and invites neither aesthetic experience nor daydreaming.

Photography, like any poetic language, communicates an interpretation of the world and must therefore surprise, arouse curiosity, and invite attentive observation.

A landscape, an object, a person, an animal, a plant, or an architectural element, by its shape, location, configuration in space, its state, whether new or degraded, its use, contains or evokes a story from which each person is free to let their imagination wander, a story that each person is free to continue.

Photography thus allows both the photographer and the viewer to construct their own vision and personal interpretation of the photographed subject.

Why is it there and like that? Why is this person here? What is she doing and how does she live?

Who left or abandoned this object here? Who lived and changed this place in this way?

How was it yesterday, and how will it be tomorrow?

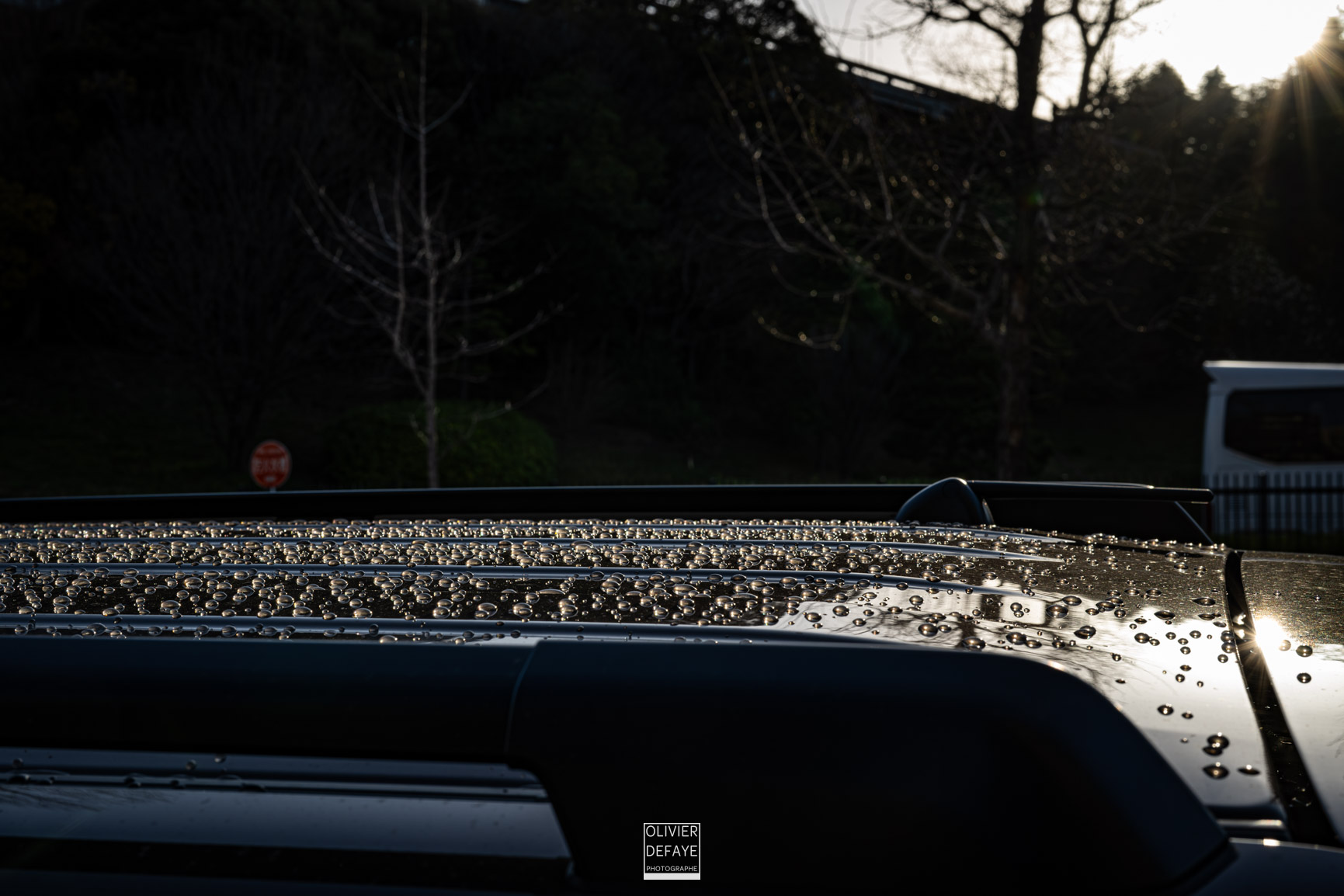

At a time of increasingly elaborate staging, heightened emotions, the extraordinary, and AI-driven image-generation tools, can't photography, on the contrary, enable us to be attentive to the simple, ordinary things in our world, like a drop of water, an abandoned object, or the look in a person's window?

Each photograph becomes an opportunity to create a unique story, to stimulate the imagination, and to transform our daily experience and poetically live the world.

“One might easily imagine that a society completely dependent on robots would become soft and decadent, eventually withering away and dying of pure boredom or, more subtly, losing the will to live.”

Foundation and Earth, 1986, Isaac Asimov

Why Image Series?

Proposing photographic series around a common theme, juxtaposing different or similar images, also invites daydreaming.

Invisible things then become familiar to us and enrich our ordinary experience.

The series Water in the City and the series Light in the City propose looking at water or light for themselves and deliberately forgetting the rest, discovering their hidden presences and their multiple facets. With photography, water transforms, and light no longer illuminates a place but exists for itself.

Photography then offers the chance to discover the extraordinary in the ordinary, to pay attention, in daily experience, to the simplest but perhaps most essential things. What would we be without water and light? It thus invites curiosity and participation in one’s environment daily, much like observing one’s garden each morning, watching for blooming flowers or the arrival of autumn.

The series Objects in the City and the series People in the City encourage us to focus on the uses of the city. How do we appropriate and use the city? Each photograph then becomes an invitation to imagination and reverie, to discovering possible worlds.

The series Gods and the City invites us to reflect on why human productions can be so numerous and varied, while the series Dogs of Tokyo attempts to capture our anthropomorphic relationship with domestic animals in the context of Japan.

“The real voyage of discovery consists not in seeing new sights, but in looking with new eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is.”

The Prisoner, 1923, Marcel Proust

References

Où en sont les théories de la photographie ?, Colloque 2015.

Univers de la fiction, Conférence de Thomas Pavel, 30 ans après, 2017.

La photographie faite avec les mains, Serge Tisseron, 2011.

L'expérience esthétique, Jean-Marie Schaeffer, 2015.

L'acte photographique, Philippe Dubois, 1983.

L'Œuvre d'art à l'époque de sa reproductibilité technique, Walter Benjamin, 1936.